This month’s Yale Climate Connections “This is Not Cool” video, following up on an earlier satellite temperature measurements video, explores the debate over the relative merits and comparative accuracy of surface thermometers vs. satellite data.

Preeminent satellite expert Carl Mears, of Remote Sensing Systems, sides with surface thermometers as consistently providing a generally more reliable record. “I would have to say that the surface data seems like its more accurate,” Mears said.

According to Zeke Hausfather, a regular Yale Climate Connections expert author and a doctoral candidate working with Berkeley Earth Surface Temperature project, “We’ve tried using just the raw data . . . globally, you get pretty much the same warming. The necessary and routine ‘adjustments’ to surface temperature data sometimes attract disproportionate general circulation media attention,” Hausfather says, but those have had very little significant impact over the last 30 years or so. “The satellite records historically have been subjected to much, much, larger adjustments over time,” according to Hausfather.

According to researcher Kevin Cowtan, of the University of York, in the United Kingdom, “The aim of adjusting the temperatures, is because what we’re not interested in is the numbers that are produced by instruments – we’re interested in the temperature of the planet. And the instruments sometimes get in the way of actually getting to the temperature, because instruments change over time.”

Cowtan and Hausfather each review a bit of climate history, as sea surface temperatures, first measured in wooden buckets, transitioned to canvas buckets, engine room intake valves, and finally, a system of modern floating buoys that give constant updates by radio signal. Each method has its own peculiar characteristics, they note.

Along with Mears, atmospheric sciences expert Kevin Trenberth of the National Center for Atmospheric Research, explains that a key source of error in the satellite record comes from having to string together data from a series of 13 satellites launched since the late 70s. “You have to cross-calibrate those satellites, and that’s probably the largest source of error in the satellite data set,” Mears says.

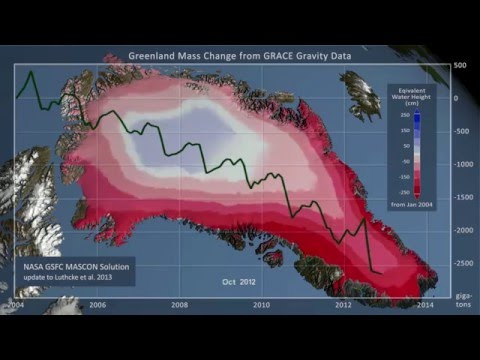

Texas A&M climate scientist Andrew Dessler and NASA oceanographer Josh Willis explain that any view of global temperature must also take account natural systems like sea ice, glaciers, ice sheets, and sea level – all of which are changing in a manner consistent with a warming planet.